Let's just give up on fundamental research or technical analysis ... the bloody fengshui chart courtesy of CLSA has been eerily accurate.

Wednesday, July 30, 2014

Sunday, July 27, 2014

Kaletsky Crushes Schiller In A Knockout

OK, its a WWF meant for financial nerds. Schiller has done very well for the knowledge base of financial economics, in particular in terms of assessing property price cycles. Not too long ago, actually, over the past 2 years, when share prices moved north, Schiller came up with his own share price "index", which is really a ratio with his selected denominators. It appeared to be very convincing that the current share prices (for the past 2 years already) sems to be way overvalued and he basically barks at us that we needed to revert to the mean, i.e. massive downside prolonged correction.

I have always considered Schiller's ratio to be too simplistic but I cannot put my finger on it. Thanks to Reuters' very own Anatole Kaletsky (previously he was the highly respected economics editor/columnist for The Times), the explanation for debunking Schiller's ratio is utterly complete. This of course in now way suggests that the present markets globally is NOT overvalued - that is a separate subject altogether.

Kaletsky's arguments are highly worthwhile to read and re read again as there are plenty of investing nuggets, and ways to look at the same thing called investments and shares.

..............................................................................................

With the stock market continuing to hit new highs almost daily

despite the appalling geopolitical disasters and human tragedies

unfolding in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria and Iraq, there has been much

head-scratching about the baffling indifference among investors. Many

economists and analysts see this apparent complacency as a symptom of a

deeper malaise: an “irrational exuberance” that has pushed stock prices

to absurdly overvalued levels.

With the stock market continuing to hit new highs almost daily

despite the appalling geopolitical disasters and human tragedies

unfolding in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria and Iraq, there has been much

head-scratching about the baffling indifference among investors. Many

economists and analysts see this apparent complacency as a symptom of a

deeper malaise: an “irrational exuberance” that has pushed stock prices

to absurdly overvalued levels.

The most celebrated proponent of this view is Robert Shiller, the Nobel Prize-winning, Yale University economist who is often credited with predicting both the 2000 stock market crash and the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble. Shiller may or may not have deserved a Nobel Prize for his academic work on behavioral economics but as a practical guide to investing, his approach has been thoroughly refuted by real-world experience.

Shiller’s status as an investment guru owes much to the timing of his book “Irrational Exuberance,” published just days before the collapse of Internet and technology stocks in March 2000. What is less widely advertised, however, is that for decades, both before and after that predictive triumph, the stock market strategy implied by his analysis has turned out to be plain wrong.

Shiller’s argument that stock prices have been inflated to irrational levels is centered on a statistic called the cyclical adjusted price-earnings ratio, or the Shiller price-earnings ratio. Conventional price-earnings ratios divide the current level of share prices by the earnings estimated by analysts for the year ahead.

This ratio for the Standard & Poor’s 500 is now around 17. On this basis many conventional analysts, including Federal Reserve economists, conclude that U.S. stock prices are reasonably valued. A price-earnings ratio of 17 implies that if companies can sustain this level of profitability, they will provide investors with annual earnings of one-17th, or 5.9 percent, which compares favorably with long-term interest rates on government bonds of around 1 percent, after adjusting for inflation.

Shiller’s price-earnings ratio, by contrast, divides the current level of stock prices by their average profits over the past 10 years (after indexing for inflation). To judge whether stock valuations are reasonable, Shiller compares them not with the prevailing level of interest rates, but with the long-term average of the Shiller ratio.

Viewed against this yardstick, Wall Street share prices look grossly overvalued. The Shiller ratio on the S&P 500 is now 26.3, far above the long-term average of 16.1, calculated by Shiller’s painstaking research on the profits of leading U.S. businesses since the late 19th century. The implication is that Wall Street is grossly overvalued and that investors should prepare for a loss of at least the 40 percent retreat required to return the ratio to 16.

In fact, the expected fall from today’s vertiginous price level should logically be much bigger than 40 percent. For the definition of an average requires that a long period of prices far above average must be balanced by an equally long period of deeply under-valued stocks.

Why then are investors not panicking? There are many theoretical objections to the Shiller’s approach. His arbitrary 10-year averaging takes no account of the length and depth of business cycles and makes no allowance for accounting write-offs. The Shiller price-earnings ratio will continue to be upwardly biased until 2019 because of the longest recession in U.S. history and the biggest-ever corporate write-offs then suffered by U.S. banks.

Even more damning is Shiller’s failure to adjust earnings for accounting changes and the impact of inflation on inventory valuations, distortions that greatly exaggerated profits in the 1970s and produced understated price-earnings ratios.

The most fundamental objection embraces all these technical arguments: Any comparison of valuations covering long periods is meaningless if it fails to take into account vast changes in technology, economic policies, interest rates, social and political structures, and taxes. Why, after all, should the returns expected today on Wall Street bear any relationship to what investors earned in the agricultural booms and busts of the 1880s or the Great Depression of the 1930s or the great inflation of the 1970s?

But leaving aside the theoretical arguments, what about the practical usefulness of the Shiller ratio as an investment tool? Recent evidence is conclusive: For the past 25 years, the Shiller ratio’s signals have been almost uniformly wrong. Since 1989, the S&P 500 has multiplied eightfold, while total returns, including dividends, have increased the value of an average equity investment 12 fold.

Investors who followed Shiller’s methodology, however, would have missed out on almost all these gains. For the Shiller price-earning ratio showed the stock market to be overvalued 97 percent of the time during these 25 years. Even during the two brief periods when the Shiller ratio was below its long-term average — in early 1990 and from November 2008 to April 200 — it never sent a clear buy signal.

Instead, Shiller’s approach suggested that the valuations in 1990 and 2009 were only just below fair value — implying there was very limited upside at the beginning of two great bull markets that saw prices multiply fivefold from 1990 to 2000, and threefold from 2009 to 2014 (so far).

The Shiller ratio’s predictive performance would have been just as bad in earlier decades if it had existed. During the equity bull market of the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the ratio would have said Wall Street was overvalued for 96 percent of the 19-year period stretching from early 1955 to late 1973.

Only in January 1974 did the Shiller price-earnings ratio move below what was then its long-run average, implying it might finally be a “safe” time to buy stocks. Straight after the Shiller ratio sent this first “buy signal” in almost two decades, Wall Street crashed by 40 percent in 12 months.

Time will tell whether the new Wall Street records are evidence of irrational exuberance or simply a reasonable response to gradual economic recovery, as suggested by Federal Reserve Chairman Janet Yellen (correctly in my view).

But one piece of evidence we can safely ignore in making this judgment is the Shiller price-earnings ratio.

I have always considered Schiller's ratio to be too simplistic but I cannot put my finger on it. Thanks to Reuters' very own Anatole Kaletsky (previously he was the highly respected economics editor/columnist for The Times), the explanation for debunking Schiller's ratio is utterly complete. This of course in now way suggests that the present markets globally is NOT overvalued - that is a separate subject altogether.

Kaletsky's arguments are highly worthwhile to read and re read again as there are plenty of investing nuggets, and ways to look at the same thing called investments and shares.

..............................................................................................

With the stock market continuing to hit new highs almost daily

despite the appalling geopolitical disasters and human tragedies

unfolding in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria and Iraq, there has been much

head-scratching about the baffling indifference among investors. Many

economists and analysts see this apparent complacency as a symptom of a

deeper malaise: an “irrational exuberance” that has pushed stock prices

to absurdly overvalued levels.

With the stock market continuing to hit new highs almost daily

despite the appalling geopolitical disasters and human tragedies

unfolding in Ukraine, Gaza, Syria and Iraq, there has been much

head-scratching about the baffling indifference among investors. Many

economists and analysts see this apparent complacency as a symptom of a

deeper malaise: an “irrational exuberance” that has pushed stock prices

to absurdly overvalued levels.The most celebrated proponent of this view is Robert Shiller, the Nobel Prize-winning, Yale University economist who is often credited with predicting both the 2000 stock market crash and the bursting of the U.S. housing bubble. Shiller may or may not have deserved a Nobel Prize for his academic work on behavioral economics but as a practical guide to investing, his approach has been thoroughly refuted by real-world experience.

Shiller’s status as an investment guru owes much to the timing of his book “Irrational Exuberance,” published just days before the collapse of Internet and technology stocks in March 2000. What is less widely advertised, however, is that for decades, both before and after that predictive triumph, the stock market strategy implied by his analysis has turned out to be plain wrong.

Shiller’s argument that stock prices have been inflated to irrational levels is centered on a statistic called the cyclical adjusted price-earnings ratio, or the Shiller price-earnings ratio. Conventional price-earnings ratios divide the current level of share prices by the earnings estimated by analysts for the year ahead.

This ratio for the Standard & Poor’s 500 is now around 17. On this basis many conventional analysts, including Federal Reserve economists, conclude that U.S. stock prices are reasonably valued. A price-earnings ratio of 17 implies that if companies can sustain this level of profitability, they will provide investors with annual earnings of one-17th, or 5.9 percent, which compares favorably with long-term interest rates on government bonds of around 1 percent, after adjusting for inflation.

Shiller’s price-earnings ratio, by contrast, divides the current level of stock prices by their average profits over the past 10 years (after indexing for inflation). To judge whether stock valuations are reasonable, Shiller compares them not with the prevailing level of interest rates, but with the long-term average of the Shiller ratio.

Viewed against this yardstick, Wall Street share prices look grossly overvalued. The Shiller ratio on the S&P 500 is now 26.3, far above the long-term average of 16.1, calculated by Shiller’s painstaking research on the profits of leading U.S. businesses since the late 19th century. The implication is that Wall Street is grossly overvalued and that investors should prepare for a loss of at least the 40 percent retreat required to return the ratio to 16.

In fact, the expected fall from today’s vertiginous price level should logically be much bigger than 40 percent. For the definition of an average requires that a long period of prices far above average must be balanced by an equally long period of deeply under-valued stocks.

Why then are investors not panicking? There are many theoretical objections to the Shiller’s approach. His arbitrary 10-year averaging takes no account of the length and depth of business cycles and makes no allowance for accounting write-offs. The Shiller price-earnings ratio will continue to be upwardly biased until 2019 because of the longest recession in U.S. history and the biggest-ever corporate write-offs then suffered by U.S. banks.

Even more damning is Shiller’s failure to adjust earnings for accounting changes and the impact of inflation on inventory valuations, distortions that greatly exaggerated profits in the 1970s and produced understated price-earnings ratios.

The most fundamental objection embraces all these technical arguments: Any comparison of valuations covering long periods is meaningless if it fails to take into account vast changes in technology, economic policies, interest rates, social and political structures, and taxes. Why, after all, should the returns expected today on Wall Street bear any relationship to what investors earned in the agricultural booms and busts of the 1880s or the Great Depression of the 1930s or the great inflation of the 1970s?

But leaving aside the theoretical arguments, what about the practical usefulness of the Shiller ratio as an investment tool? Recent evidence is conclusive: For the past 25 years, the Shiller ratio’s signals have been almost uniformly wrong. Since 1989, the S&P 500 has multiplied eightfold, while total returns, including dividends, have increased the value of an average equity investment 12 fold.

Investors who followed Shiller’s methodology, however, would have missed out on almost all these gains. For the Shiller price-earning ratio showed the stock market to be overvalued 97 percent of the time during these 25 years. Even during the two brief periods when the Shiller ratio was below its long-term average — in early 1990 and from November 2008 to April 200 — it never sent a clear buy signal.

Instead, Shiller’s approach suggested that the valuations in 1990 and 2009 were only just below fair value — implying there was very limited upside at the beginning of two great bull markets that saw prices multiply fivefold from 1990 to 2000, and threefold from 2009 to 2014 (so far).

The Shiller ratio’s predictive performance would have been just as bad in earlier decades if it had existed. During the equity bull market of the 1950s and 1960s, for example, the ratio would have said Wall Street was overvalued for 96 percent of the 19-year period stretching from early 1955 to late 1973.

Only in January 1974 did the Shiller price-earnings ratio move below what was then its long-run average, implying it might finally be a “safe” time to buy stocks. Straight after the Shiller ratio sent this first “buy signal” in almost two decades, Wall Street crashed by 40 percent in 12 months.

Time will tell whether the new Wall Street records are evidence of irrational exuberance or simply a reasonable response to gradual economic recovery, as suggested by Federal Reserve Chairman Janet Yellen (correctly in my view).

But one piece of evidence we can safely ignore in making this judgment is the Shiller price-earnings ratio.

Thursday, July 24, 2014

Best Omakase Ever

Omakase in Japanese means according to the chef's wishes. What he/she sees fit and best to be served that best exemplify their skills and produce selection.

Omakase in Japanese means according to the chef's wishes. What he/she sees fit and best to be served that best exemplify their skills and produce selection. A simple start, Japanese sweetened pickled barley on Japanese cucumber, refreshing. The beautiful colour of the uni indicates freshness laced with caviar. Plus a light vinegary sweet broth with some unique stems from a rare veggie which slips my mind for now.

A true test of any really good Japanese restaurant is to go sit at the main counter table and face the chef asking for omakase. I have had plenty of good Japanese dinners, even the renowned Ryugin and Kanda in Tokyo. However, my recent meal at Hanazen @ Jaya One tops the lot and that is no faint praise.

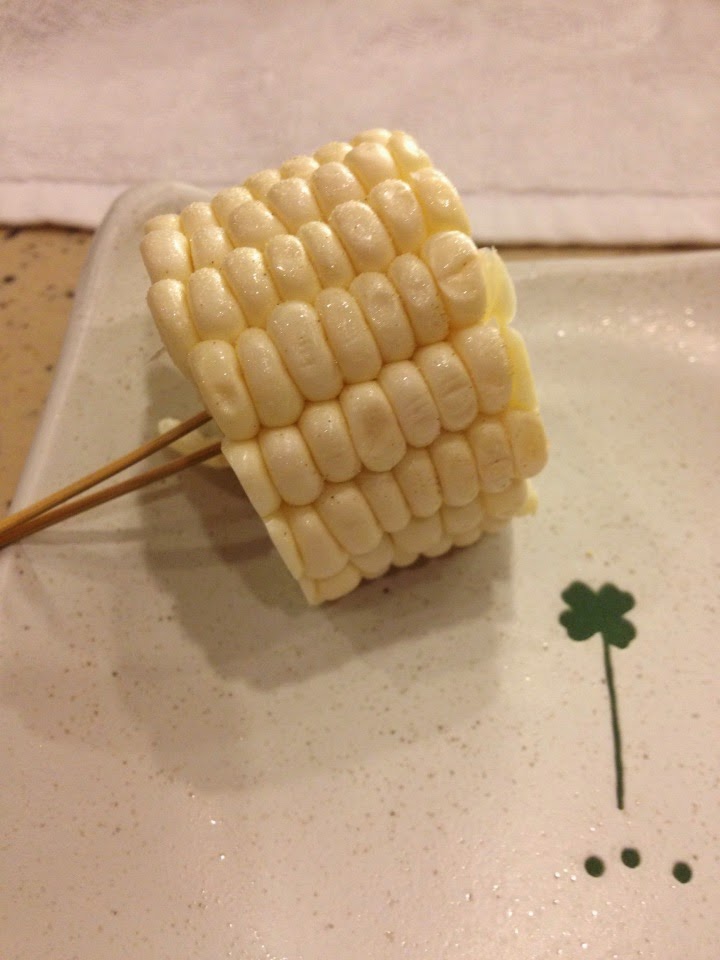

A true test of any really good Japanese restaurant is to go sit at the main counter table and face the chef asking for omakase. I have had plenty of good Japanese dinners, even the renowned Ryugin and Kanda in Tokyo. However, my recent meal at Hanazen @ Jaya One tops the lot and that is no faint praise.A palate cleanser of sorts, chilled young corn from Hokkaido, so sweet and crunchy like a fruit. This is only in season one month in a whole year, exceptional.

I have written about Hanazen before. They are eternally packed for lunch owing to their (not cheap) but very tasty and value for money bentos. But for the fix, go at night and ask for omakase. The omakase ranges from RM300-500 pp but let me assure you its value for money and is like a trip around Japan's loveliest seasonal bounty.

I have written about Hanazen before. They are eternally packed for lunch owing to their (not cheap) but very tasty and value for money bentos. But for the fix, go at night and ask for omakase. The omakase ranges from RM300-500 pp but let me assure you its value for money and is like a trip around Japan's loveliest seasonal bounty.The exquisite Okayama grapes, that package alone costs over RM120. I got to have 3 for my desserts plate ... lol.

This horrible looking fish from Kyushu, the Akamutze, but oh so sweet and delicate.

Lightly seared Kagoshima beef on sushi rice, great. But next to it was the single best piece of sushi I have ever had, flounder belly, beyond words, much better than any tuna toro.

I love almond and Hanazen's home made almond jelly is to die for, plus the 3 miserable Okayama grapes ... and wait for it, the famous Shizuoka musk melon (its so sweet I thought it was syrup).

Make sure the chef owner is there, my nick name for him is Mun-Mun ...lol.

Friday, July 18, 2014

Thursday, July 10, 2014

The Experts (Are Way Off)

No amount of back data, simulation ... can predict future events accurately. All those who study statistical distribution and variance analysis can only guess at best. In much the same mould, are the experts' views and predictions about investments (mine included). Hence, take experts' views with a large bucket of sodium.

Wednesday, July 09, 2014

The Sporting World Is So Biased

OK, with Brazilian supporters reeling, my friend at BFM said Samba became Sambal after being pounded to a pulp ... with something fishy, oh, its belacan ... and it goes very well with frankfurters. I did not regard Brazil as a threat as was discussed in my previous World Cup posting, they are like many Penang hawker food stalls, easy to champion but generally over rated.

The sporting world is so biased. If you had switched the jerseys, and the same people played, ending with Brazil winning 7-1, the reaction by most watchers and the media would have been ecstatic. But no, just because they were Germans, they were referred to as clinical, well drilled ... Thats a load of bs, if they played under the banner of Brazil, they would have been referred to as magical, tearing the defence apart, making them look like schoolboys, etc...

The sporting world is so biased. If you had switched the jerseys, and the same people played, ending with Brazil winning 7-1, the reaction by most watchers and the media would have been ecstatic. But no, just because they were Germans, they were referred to as clinical, well drilled ... Thats a load of bs, if they played under the banner of Brazil, they would have been referred to as magical, tearing the defence apart, making them look like schoolboys, etc...

The sporting world is so biased. If you had switched the jerseys, and the same people played, ending with Brazil winning 7-1, the reaction by most watchers and the media would have been ecstatic. But no, just because they were Germans, they were referred to as clinical, well drilled ... Thats a load of bs, if they played under the banner of Brazil, they would have been referred to as magical, tearing the defence apart, making them look like schoolboys, etc...

The sporting world is so biased. If you had switched the jerseys, and the same people played, ending with Brazil winning 7-1, the reaction by most watchers and the media would have been ecstatic. But no, just because they were Germans, they were referred to as clinical, well drilled ... Thats a load of bs, if they played under the banner of Brazil, they would have been referred to as magical, tearing the defence apart, making them look like schoolboys, etc...

Tuesday, July 08, 2014

European & Japanese Equities Gaining Favour

Fiscal measures announced by the European Central Bank, European equities should finish the year in a better shape despite increased volatility. The credible package of measures should nudge growth in the euro zone up a gear, as businesses should reap the benefit of easier access to funds, while the weaker euro would promote exports. On the flip side, some remained to be watchful of the current hunger for high yields on the part of investors, as there are echoes of the 2005-07 scenario in the market. Europe is still fighting deflation like most of the rest of the world (with the exception of emerging markets).

Fiscal measures announced by the European Central Bank, European equities should finish the year in a better shape despite increased volatility. The credible package of measures should nudge growth in the euro zone up a gear, as businesses should reap the benefit of easier access to funds, while the weaker euro would promote exports. On the flip side, some remained to be watchful of the current hunger for high yields on the part of investors, as there are echoes of the 2005-07 scenario in the market. Europe is still fighting deflation like most of the rest of the world (with the exception of emerging markets). Some may cite low GDP growth as a basis for under performance of equity markets but as many studies have shown, there is no correlation with the stock market. This is largely due to its forward discounting valuation platform.

The UK markets stood out as the first European country to be adjusting its rate upwards in what is a fine balancing act on the part of the Bank of England, because it is one of the most indebted places in the world, not to mention the housing boom which is not easy to deflate. Previously in deep recession, these countries have now bottomed out and turned for the better, significantly Spain, Greece and Portugal.

Political uncertainties are merely noises that do not significantly impact on his strategy. Dysfunctional governments all over the place, Malaysia is a prime example of equity markets working in spite of it.

Funds Like Abe

Funds Like AbeAs prime minister Shinzo Abe's "Abenomics" continues to work to boost Japan's economy, the country's equity funds may be a risky but profitable choice for mandatory provident fund investors. Japanese equity funds were the biggest performers last year when Abenomics started taking effect, with returns reaching 33 percent.

But the situation then changed, with the funds recording negative returns since the beginning of the year. Average returns amounted to negative 3.55 percent for the first half. This came as the Nikkei slumped 9 percent in the first quarter. However, a recovery is under way in Japan.

A sales tax hike in April triggered a 12 percent drop in sales that month. But the drop eased to just 4 percent in May, as retail sales warmed up again.

Tokyo is optimistic that the economy will continue to improve and has raised its estimates on private consumption.

Abe's "third arrow" of sweeping reform - like the creation of "national strategic economic growth areas" in Tokyo, Kansai and Fukuoka - also helped fuel a rally in Japanese stocks.

That came after the first and second arrows of Abenomics - fiscal stimulus and monetary expansion - achieved considerable success in spurring economic renewal.

Consumer prices in Japan rose at an annual rate of 3.4 percent in May, the fastest pace in 32 years, and the unemployment rate is 3.5 percent - the lowest since 1997.

Data show that Japanese equity funds received total capital inflow of about US$12.8 billion as of mid-June. Net capital outflow for the second week that month amounted to about US$170 million. As investors have started to bring in capital since May, the market is assumed to be regaining confidence in Japan. People have started to reevaluate the effect of Abenomics, as the sales tax hike has not brought the expected slump in share prices. Investors have started to regain interest in Japanese stocks and liquidity is increasing and flowing into tangible assets.

Data show that Japanese equity funds received total capital inflow of about US$12.8 billion as of mid-June. Net capital outflow for the second week that month amounted to about US$170 million. As investors have started to bring in capital since May, the market is assumed to be regaining confidence in Japan. People have started to reevaluate the effect of Abenomics, as the sales tax hike has not brought the expected slump in share prices. Investors have started to regain interest in Japanese stocks and liquidity is increasing and flowing into tangible assets.Friday, July 04, 2014

LIVE - Music Inspired By Wong Kar Wai's In The Mood For Love

Music inspired by Wong Kar Wai's movies, or is it the other way around. Methinks in most cases, Wong fell in love with the songs, and he basically recreated the mood and setting to suit the songs even. Nonetheless, this should be a prime live event, great singers (Serena Chong and May Mow) coupled with strong arrangement by Tay Cher Siang, and I am certain that there will a big screen with movie scenes to accompany the live performance.

Dates: 9 & 10 July, Wednesday & Thursday

Venue: No Black Tie, Jalan Mesui, KL

Time: 9.30pm

Cover: RM60

To make reservations, please contact Kylie 016.287.7538

Dates: 9 & 10 July, Wednesday & Thursday

Venue: No Black Tie, Jalan Mesui, KL

Time: 9.30pm

Cover: RM60

To make reservations, please contact Kylie 016.287.7538

Asset Class Returns As At 30 June 2014

June was another strong month for returns across the board. Red

ink was banished among the major asset classes for the third time this

year on a monthly calendar basis. What that meant was that investors are putting their funds to work, finally, this is just a small tide turning, as things stand still way too much liquidity is on the sidelines. Hence we may be surprised for a sustained surge plus higher volatility of course.

The big winner last month: emerging market stocks, which climbed 2.7% on a total return basis in June–the fifth straight monthly gain for this slice of equities. This was a significant trend as funds are finally willing to move to emerging markets equities alongside a pretty solid run in US stocks. If you note the monthly and YTD returns, the run up in emerging market stocks closely mirrors the oil prices.

Given the bullish tailwind, it’s no surprise to find that June was kind to the Global Market Index (GMI), an unmanaged benchmark that holds all the major asset classes in market-value weights. GMI posted its fifth straight monthly gain, rising 1.4% in June. For the year so far, GMI is up a solid 5.7 %.

Even more impressive, GMI’s trailing one-year return is 17%–the highest year-over-year comparison for the benchmark since the mid-way mark in 2011. On a trailing five-year basis, GMI’s 10.9% annualized total return is the most since May 2008. In short, bullish momentum has paid off handsomely.

The big winner last month: emerging market stocks, which climbed 2.7% on a total return basis in June–the fifth straight monthly gain for this slice of equities. This was a significant trend as funds are finally willing to move to emerging markets equities alongside a pretty solid run in US stocks. If you note the monthly and YTD returns, the run up in emerging market stocks closely mirrors the oil prices.

Given the bullish tailwind, it’s no surprise to find that June was kind to the Global Market Index (GMI), an unmanaged benchmark that holds all the major asset classes in market-value weights. GMI posted its fifth straight monthly gain, rising 1.4% in June. For the year so far, GMI is up a solid 5.7 %.

Even more impressive, GMI’s trailing one-year return is 17%–the highest year-over-year comparison for the benchmark since the mid-way mark in 2011. On a trailing five-year basis, GMI’s 10.9% annualized total return is the most since May 2008. In short, bullish momentum has paid off handsomely.

Wednesday, July 02, 2014

Wong Fu

Have you heard of Wong Fu Productions? They are a bunch of Asian Americans trying to tear down stereotypes by making sensitive wonderful storytelling videos/films acted primarily by Asian Americans. We do not see so much of ourselves being portrayed by Western films and TV shows. There are Chinese (Vietnamese / Hindi / Tamil) movies and TV shows but what about those who speak mostly English. In many ways, their videos' popularity point to a huge number of us belonging to that category. Great storytelling, sensitive scripting ... I am sure they will be making a real full length movie soon. I mean, they already got Wang Lee Hom to do a short film with them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)